The large black roller gate is about four meters wide and five meters tall. Anyone standing in the TRUMPF development building at the Ditzingen headquarters can hardly miss it. A small card reader hangs next to the gate. When a TRUMPF employee holds up their company ID card, almost everyone is greeted with the same lengthy beep. If the reader flashes red, it means “Access Denied”. A sign next to the gate explains why many people cannot gain entry here. It states “Testing area - entry and photography prohibited”. This is where TRUMPF is researching the future of its technologies.

A call to Jürgen Brandt is our only way through the gate. The black gate opens almost immediately once the receiver is hung up. It opens to a large hall with around 25 TRUMPF machines. Laser cutting systems, welding machines and bending cells are not so much seen as hinted at - because the employees have dismantled them into their individual parts. Screws are being inserted, installations are taking place, and testing is being performed throughout the hall. Jürgen Brandt beams and waves us in as if to say: “Come on, don’t be shy”.

He knows his way around: Jürgen Brandt has been working for TRUMPF for 50 years, with 40 of those years spent in the testing area in Ditzingen.

Bringing TRUMPF machines to life

This is the 65-year-old's realm - the testing lab and prototype design department at TRUMPF. And it has been his realm for almost five decades. “This year I am celebrating 50 years of service with the company,” he says proudly and looks around: “I know this place down to the last centimeter and, more importantly, every single machine.” He began his apprenticeship as a toolmaker at TRUMPF in September 1973. Since then, the devoted family man has not been lured away from his hometown of Ditzingen and certainly not from “his TRUMPF”. Jürgen Brandt laughs: “My schoolmates were always changing employers. Maybe their jobs were simply boring. I have always had a lot of variety. In all these years, not a single day has given me a reason to look elsewhere.”

Tinker with it, try it out, and just do it - this was Brandt's philosophy from day one. The testing area was and is exactly the right place for this. He transferred to this department immediately after his training and initially worked as a lathe operator and miller. He later became a master, then a team leader and today he is the coordinator for the laser flatbed machines. “From 1982 to today, I have helped bring 74 TRUMPF machines into the world,” says Brandt, pointing to an Excel list that he is holding in his hand. Here he has documented exactly which new machines he and his colleagues worked on, and in which year. The first hydraulic punching head, the first CO2 laser and the first flatbed machine with a solid-state laser can be found in the overview. “Today there isn’t a machine type at TRUMPF that I haven’t had my hands on,” says Brandt happily. He has built the machines, tested them, looked for errors, improved them, introduced new ideas and even registered a patent. Always in close consultation with the developers and designers, but also always taking into account the needs of the customer and the service employee. Jürgen Brandt requires a 360-degree view for his work.

36 gigabytes of memories

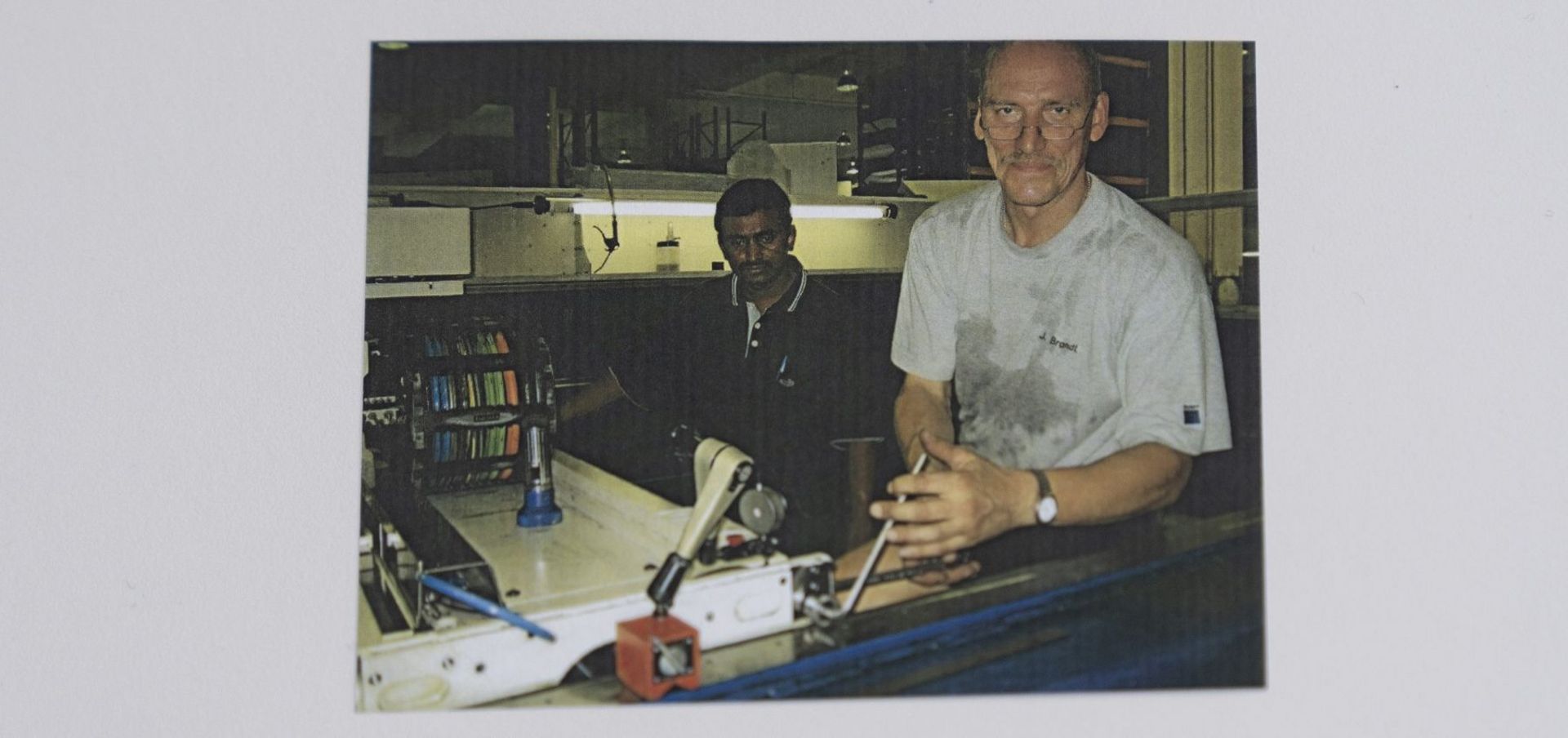

In the middle of the testing hall there is a rectangular container with windows. A look through the glass reveals that meetings usually take place here. The room is austere. It consists of a large table with a dozen chairs around it and a mobile screen at the front. Jürgen Brandt has laid out countless photos on the table. This is a photo history of his time at TRUMPF. “But that’s not all,” he says, opening his laptop and clicking through some folders with dates: “I have photos of my prototype builds, my stays abroad and my trade fair appearances,” he says. The drive shows over 20,600 files and 36 gigabytes of data.

Traveling the world with toolbox in hand

The highlights of his photo collection: Memories from the 17 countries he visited on TRUMPF business trips, including Australia, South Africa, Singapore and the USA. “Actually, my workstation was in the testing hall in Ditzingen. However, since I knew the TRUMPF machines so well, my service colleagues always contacted me when they didn't know what to do." Jürgen Brandt was particularly known for one specialist area: he was an expert in machine collisions. If a machine somewhere in the world experienced a collision between the sheet metal and the cutting head, he was called in. Sometimes to the chagrin of his bosses. “Service employees would call and casually let me know: ‘Jürgen, you’ve earned a trip’. And off I went. Often I didn’t even know exactly where I was going, I just got on a flight,” remembers Brandt. In this way, he has seen half the world.

It's not easy to say goodbye

While Jürgen Brandt loved adventure abroad, he appreciated the good collaboration at home. “I still remember how our boss at the time, Berthold Leibinger, kept stopping by my workstation. He wanted to know when the next machine would be ready; after all the business depended on it,” says Brandt. To this day he has never tired of devoting himself to new challenges every day. “For me there are no problems, just things that don't work 100 percent. “I’m a tinkerer who’s not happy until I’ve found the solution,” he says with a smile. He points to a laser cutting system in the testing hall. On this machine he is currently optimizing the flow of the cables. It is likely one of his last projects. He will retire in October.

“Of course I’m looking forward to it, at some point it's a good thing. I have five grandchildren, love to play the drums, and I enjoy tinkering at home. But TRUMPF is my second home. I live for TRUMPF," he says, visibly moved and smiling: "I don't know anything other than riding my bike to TRUMPF every day." He packs up his pile of pictures on the table, closes the photo folder on the laptop, and walks toward the black roller gate. He presses the gate opener and the roller gate cinches open. Brandt walks through and says: “Sometimes I should have enjoyed my time here even more.” After a few seconds, a muffled noise: the black roller gate closes behind Jürgen Brandt. And the testing hall is locked again.